The art of editing as practiced by America's greatest editors

|

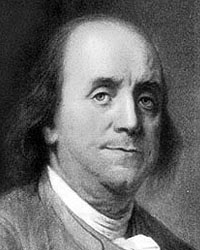

Benjamin Franklin, 1706-1790

|

|

Benjamin Franklin

"Printer" is the only occupation that Franklin listed in his own epitaph. The word speaks

to his life-long belief in the importance of the written word, produced in quantity for a mass audience.

He is the perfect exemplar of editor as renaissance man: Equally well-informed about politics, history,

science and literature; a master of serious argument but just as comfortable writing satire and homespun

jokes and proverbs.

Creator of America's first lending library and its first nationwide communication system, the

colonial post office, Franklin had a practical man's focus on better ways to distribute information.

As a master of the press, his era's mass communication technology, he remains an inspiration for today's

editors who struggle to stay current with our trade's digital tools. His published output ranged from books

and magazines to pamphlets, newspapers and the popular Poor Richard's Almanac. His editor's eye helped a

revolutionary movement become a new nation. The most famous example is Franklin's collaboration with Thomas

Jefferson and John Adams to refine the original drafts of the Declaration of Independence.

See the process as it took place in 1776:

to Declaration draft. to Declaration draft.

Though these words never appeared on his tomb, Franklin wrote his own epitaph as a young man,

with the work of editing and printing a metaphor for life: "The Body of B. Franklin Printer; Like the Cover

of an old Book, Its Contents torn out, And stript of its Lettering and Gilding, Lies here, Food for Worms.

But the Work shall not be wholly lost: For it will, as he believ'd, appear once more, In a new & more

perfect Edition, Corrected and Amended By the Author."

|

|

Franklin applies his editorial genius to the Declaration of Independence in this scene from

HBO's series "John Adams." This YouTube clip (sorry for poor quality) shows Franklin and Adams advising Thomas

Jefferson about the Declaration's final wording.

to clip from "John Adams." to clip from "John Adams."

|

|

|

|

|

Maxwell Perkins, 1884-1947

|

Maxwell Perkins

It's hard to imagine American literature without F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway

or Thomas Wolfe. But those iconic novelists might never have been published without the stubborn advocacy

of Maxwell Perkins, the great 20th-century book editor. From 1910 to 1947, he worked for the old-line

publishing house Charles Scribner's Sons, shaking up the establishment by seeking out unknown young talent.

Fitzgerald was Perkins' first big discovery. He had to work with the young author to revise

a rejected manuscript, lobbying hard inside his own company to get it published as This Side of Paradise.

Fitzgerald's later works, especially his masterpiece The Great Gatsby, were shaped and refined by Perkins'

editorial suggestions.

His next major battle was to get Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises published, against conservative

colleagues objecting to profanity in its dialogue. By 1929, when Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms topped

the best-seller list, Perkins' reputation for literary judgment was unquestioned.

Perkins' greatest challenge came from a difficult author. Unlike William Faulkner, who famously

commented, "In writing, you must kill all your darlings," Wolfe couldn't bear to cut a single sentence from

his vast output. Perkins struggled for years to persuade Wolfe to accept major cuts to Look Homeward, Angel

and Of Time and the River.

Diplomacy is necessary for a book editor. Perkins didn't have to fake it. He had a reputation

as genuinely considerate, but also as a great judge of good writing and of narrative structure. His lasting fame

comes from his tireless work as a mentor, coach and advocate for writers.

For a dramatized version of Maxwell Perkins' relationship with Thomas Wolfe, see this trailer

for the upcoming movie "Genius." Colin Firth plays Perkins and Jude Law plays Wolfe.

For a dramatized version of Maxwell Perkins' relationship with Thomas Wolfe, see this trailer

for the upcoming movie "Genius." Colin Firth plays Perkins and Jude Law plays Wolfe.

to trailer for "Genius." to trailer for "Genius."

|

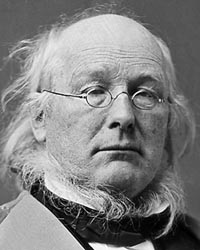

Horace Greeley, 1811-1872

|

|

Horace Greeley

Focused on serious news reporting, as well as advocacy for such

great causes as abolishing slavery, Greeley was his era's greatest editor. A sometime ally

to Abraham Lincoln, yet often a thorn in the president's side, Greeley was an important

shaper of public opinion before and during the Civil War and its turbulent aftermath.

William Seward, who became one of the famous "Team of Rivals" in Lincoln's cabinet,

described Greeley as "singularly clear, original, and decided, in his political views and theories."

Like Ben Franklin a century earlier, Greeley began his career as a printer's apprentice.

After several jobs in print shops, he landed in New York while still in his teens to work as an

editor. His first great cause was the "Log Cabin" campaign that elected William Henry Harrison as

president in 1840. But it wasn't just his causes and his political maneuverings that made Greeley's

reputation: It was how he edited his New York Tribune.

He had a talent for hiring the best reporters to do important news coverage, and

finding top-notch feature writers, too. Unlike many of his 19th-century competitors (and present-day

print and TV "news" managers,) Greeley wasn't interested in scandal, crime news, or trivial coverage of

celebrities. His Tribune won its reputation, and built its readership, with good taste,

intellectual rigor, and accurate political reporting. He aimed his paper at serious-minded readers,

and gave them lavish coverage of ideas, in the form of books and lectures.

|

|

|

|

William Shawn, 1907-1992

|

William Shawn

Originally a flippant, light-weight magazine, The New Yorker became the influential,

respected journal it is today through years of work by William Shawn. Starting as a staff editor under founder

Harold Ross, Shawn became editor after Ross' death in 1952. He held that job for a remarkable 35 years until

he was pushed out by new corporate owners in 1987.

It was Shawn who persuaded Ross to devote an entire issue of the magazine to John Hersey's

Hiroshima, giving American readers an unforgettable feeling for what nuclear war really meant. Almost

two decades later, in 1965, his publication of Truman Capote's In Cold Blood set new standards for both

literature and reporting.

With something of the same impact Horace Greeley's New York Tribune had a century before, Shawn's

New Yorker helped set the national agenda. In the early 1960s, it published dramatic writings by James

Baldwin on racial conflict and by Rachel Carson on environmental degradation. In its non-fiction reporting and

reviews, the magazine made important contributions to awareness of the Holocaust and of poverty in America.

Shawn's editing won him respect and affection from the writers he published. He was a stickler for

accuracy and a master of detail, but rarely impatient. The author Renata Adler commented, in a remark

repeated in Shawn's New York Times obituary, "He knows when to leave a strong piece alone. If there

really are weak parts, though, he invariably finds them; then of course you can fix them in your own way."

|

|